This is probably going to sound stupid (or at least obvious) to anyone who already knows anything about Bram Stoker and/or Dracula, but: Wow, y’all, this book is where Dracula comes from. As in, like, this is his first appearance; Bram Stoker, in his 1897 novel, created the character Dracula. And Van Helsing. Like how Walt Disney created Mickey Mouse.

Sure, fine, cue Captain Obvious. I’m sure most people already knew that. But Dracula has appeared in so many pieces of media over the last 124 years that I always figured he was one of those public domain legends like Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster. I mean, my daughters LOVE Dracula—they know him as a family-oriented cartoon character voiced by Adam Sandler. Personally, my first experience with Dracula was whipping him to death as a Belmont in Castlevania, the series of video games from Konami.

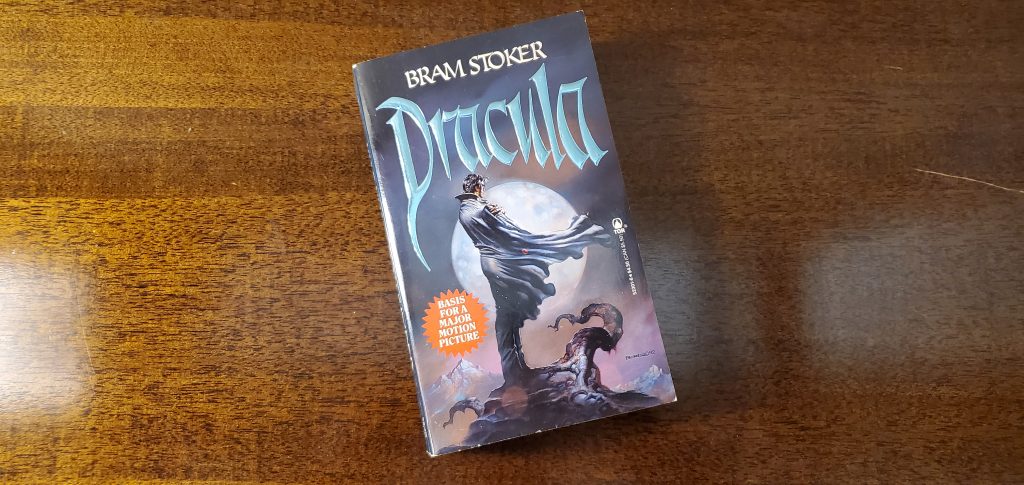

Yes, I’ve always known Bram Stoker wrote a book called Dracula, and yes, I know a movie came out when I was seven years old called Bram Stoker’s Dracula (though I haven’t seen it), but I thought that was like, you know, Disney’s Cinderella or Peter Jackson’s King Kong—merely pointing out it’s that person’s interpretation of the story. (No, I didn’t know back then that Mr. Stoker passed away in 1912.)

ANYWAY, the point is, this is the book that introduced the character Dracula, before he became the generic vampire in a million different movies, cartoons, video games, and cereal boxes.

And it’s quite good. Mostly. Much of the dialogue shows tremendous age, and the shifting, protracted spotlight on the lives of Mina, Lucy, and Reinhart sometimes distract from the main thread. From chapter 5 onward, struggling to keep my eyes open while reading their flowery letters to each other, I threw in the towel and grabbed the audio book. On one hand, their letters and journal entries are so conversational, with tiny, relevant details inconspicuously peppered throughout, that they feel like genuine documents. On the other hand, forcing myself to read them felt like some puritanical gesture of self punishment (to borrow a phrase from Alistair Reynolds). I’ve never said this about a book before, but these days an abridged version of Dracula would probably make for a better read.

Dracula is an “epistolary novel,” a storytelling technique likely more familiar to my generation as “found footage;” a long collection of letters and journal entries from Johnathan Harker, Mina Murray, Lucy Westenra, Abraham Van Helsing, and many more, all chronicling Count Dracula’s move from Transylvania to London—and his retreat back to Transylvania. Although this book is super old, beware if you have plans to read it for I will now spoil the, er, decidedly unholy hell out of it.

Things certainly start with a bang. Chapters 1–4, Jonathan Harker’s journal entries, detail his visit to Dracula’s castle to consult on the count’s move to London. He presently becomes something of a prisoner in the castle, and is compelled to explore whenever he can. Every word of these first four chapters is solid gold. The castle is mysterious and creepy, and seems to have a different layout every time Harker leaves his room. (I wonder if this inspired some of the level design in the Castlevania video games; most of the games take place in Dracula’s castle, but the layout is always different from game to game.) Harker has several terrifying run-ins, and eventually becomes aware Count Dracula is a vampire. He barely manages to escape, and winds up delirious at a convent.

Chapters 5 and 6 switch abruptly to letters between Mina (Harker’s fiancée) and Lucy, plus their diaries, and God help me, it was just so boring. It likely has something to do with the tongue of the day being what it is, but their overly formal banter felt far longer than its 20 pages. This is where I switched to the audio book, and I’m glad I did—it’s narrated by Alan Cumming and Tim Curry, among others. Here’s a single paragraph of Mina’s diary, to give a taste:

Lucy met me at the station, looking sweeter and lovelier than ever, and we drove up to the house at the Crescent in which they have rooms. This is a lovely place. The little river, the Esk, runs through a deep valley, which broadens out as it comes near the harbour. A great viaduct runs across, with high piers, through which the view seems somehow further away than it really is. The valley is beautifully green, and it is so steep that when you are on the high land on either side you look right across it, unless you are near enough to see down. The houses of the old town—the side away from us—are all red-roofed, and seem piled up one over the other anyhow, like the pictures we see of Nuremberg. Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey, which was sacked by the Danes, and which is the scene of part of “Marmion,” where the girl was built up in the wall. It is a most noble ruin, of immense size, and full of beautiful and romantic bits; there is a legend that a white lady is seen in one of the windows. Between it and the town there is another church, the parish one, round which is a big graveyard, all full of tombstones. This is to my mind the nicest spot in Whitby, for it lies right over the town, and has a full view of the harbour and all up the bay to where the headland called Kettleness stretches out into the sea. It descends so steeply over the harbour that part of the bank has fallen away, and some of the graves have been destroyed. In one place part of the stonework of the graves stretches out over the sandy pathway far below. There are walks, with seats beside them, through the churchyard; and people go and sit there all day long looking at the beautiful view and enjoying the breeze. I shall come and sit here very often myself and work. Indeed, I am writing now, with my book on my knee, and listening to the talk of three old men who are sitting beside me. They seem to do nothing all day but sit up here and talk.

If that’s up your alley, then more power to you, but I was glad to stick it in my ear and let the narrator barrel through it. I went back and forth between paper and audio after that, and I greatly enjoyed reading the gooshy parts on paper. Chapter 7 features the ship log of the Demeter, and it’s more gold. Dracula is a passenger of the ship, you see, along with his boxes of dirt, and terrorizes the crew. The captain of the ship ends his log by tying his hands to the wheel so it makes it to port. It’s chilling and oh-so-good. Then the books goes back to Mina and Lucy talking about suitors, but adds the wrinkle of Lucy’s sleepwalking and of her suddenly deteriorating health. Things pick up again when Abraham Van Helsing shows up, though his dialogue (especially when praising one of the women) can be just as difficult to trudge through. I won’t quote any of his long speeches (check out the end of chapter 14 if you’re curious) but just for laughs, (for I hope we won’t hold it against this old book), here’s a “compliment” Van Helsing pays to Mina regarding her intelligence in chapter 18: “Ah, that wonderful Madam Mina! She has [a] man’s brain.”

Anyway, after a series of blood transfusions to help the anemic Lucy, she passes away. It turns out her frequent sleepwalks around town left her vulnerable, repeatedly, to the new-in-town Count Dracula. When Van Helsing concludes that she herself has become a vampire (one who operates as such only as a sleepwalker, btw, and feeds exclusively on children), he visits her tomb with a cadre of her erstwhile suitors (plus her erstwhile fiancé, Arthur) to put an end to her undead sleepwalking.

Also woven throughout the book from chapters 5–22 is a curious character named Renfield, “Sanguine temperament; great physical strength; morbidly excitable,” whose story is usually communicated to us by another of Lucy’s erstwhile suitors, Dr. John Seward. I’ll skip any quotes regarding Renfield (though he does get horribly brutalized by the big man himself, so check out chapter 21 if you want those grisly details). He’s a patient of Seward’s at a private lunatic asylum, and he’s, well, he’s pretty gross. He eats flies, spiders, possibly birds and rats when he can, ostensibly to “gain life.” I spent a lot of time wondering what purpose he served in the overall story, but it seems from chapter 20 that his purpose is to communicate to the reader how Dracula functions, or at least to give Seward, etc., a way to comprehend it. It is a bit much (and in the end reminded me of Christopher Nolan’s movie Batmen Begins, where he spends nearly the entire movie justifying how Bruce Wayne put that suit together) but it was necessary, especially for readers of the 19th century, before Dracula became synonymous with “vampire.”

To recap thus far, Dracula moves to London after leaving Harker for dead in Transylvania and murdering the crew of the Demeter on the ride over. Once there he makes like Templeton at the fair, one of his victims being the poor sleepwalker Lucy, who turns into a vampire herself before Van Helsing and the gang of suitors puts her out of her misery.

Later, with the traumatized Harker back at home, he and Mina now a married couple, the group concludes Dracula is in London and they plot to destroy him. When Dracula gets wise to this, the men realize all too late that Mina is targeted in retaliation. They rush to the Harker residence, only to discover Dracula has forced Mina to drink his blood. The group then travels to Dracula’s mansion at Piccadilly Circus and wait for him, for they suspect he’s retreating back to Transylvania, but are unfortunately caught slightly unprepared in chapter 23, when Dracula catches them in the act. They attack the vampire, but manage only to knock a whole bunch of gold coins and papers from him arms. He all but laughs off their attempts and darts away.

In short, things go really badly. As you can tell from the gold and papers Dracula had with him, he decided this modern world was actually a bit too much for him, so he turned tail and ran back to his castle. “We can know now what was in the Count’s mind, when he seize that money… He meant escape,” Van Helsing says of Draula. “Hear me, ESCAPE! He saw that with but one earth-box left, and a pack of men following like dogs after a fox, this London was no place for him. He have take his last earth-box on board a ship, and he leave the land. He think to escape, but no! we follow him. Tally Ho!” The gang regroups and plots another confrontation with Dracula, and here, with seconds before the sun sets, they finally do the thing:

As I looked, the eyes saw the sinking sun, and the look of hate in them turned to triumph.

But, on the instant, came the sweep and flash of Jonathan’s great knife. I shrieked as I saw it shear through the throat; whilst at the same moment Mr. Morris’s bowie knife plunged into the heart.

It was like a miracle; but before our very eyes, and almost in the drawing of a breath, the whole body crumble into dust and passed from our sight.

I shall be glad as long as I live that even in that moment of final dissolution, there was in the face a look of peace, such as I never could have imagined might have rested there.

The Castle of Dracula now stood out against the red sky, and every stone of its broken battlements was articulated against the light of the setting sun.

And there you have it. Rest in peace Dracula (And Lucy, and Quincy Morris—yet another erstwhile suitor). Overall, great book. At 160,000 words, many of them not nearly as readable as they likely were 124 years ago, I struggle to recommend it, but I’m happy I read/listened to it. Maybe you will be too.

If you’ve a stomach for more of the gooshier parts, see below:

The scene where Jonathan Harker discovers Dracula’s three wives, plus a little bit from the next chapter:

[Harker’s Journal:] I was not alone. The room was the same, unchanged in any way since I came into it; I could see along the floor, in the brilliant moonlight, my own footsteps marked where I had disturbed the long accumulation of dust. In the moonlight opposite me were three young women, ladies by their dress and manner. I thought at the time that I must be dreaming when I saw them, for, though the moonlight was behind them, they threw no shadow on the floor. They came close to me, and looked at me for some time, and then whispered together. Two were dark, and had high aquiline noses, like the Count, and great dark, piercing eyes that seemed to be almost red when contrasted with the pale yellow moon. The other was fair, as fair as can be, with great wavy masses of golden hair and eyes like pale sapphires. I seemed somehow to know her face, and to know it in connection with some dreamy fear, but I could not recollect at the moment how or where. All three had brilliant white teeth that shone like pearls against the ruby of their voluptuous lips. There was something about them that made me uneasy, some longing and at the same time some deadly fear. I felt in my heart a wicked, burning desire that they would kiss me with those red lips. It is not good to note this down, lest some day it should meet Mina’s eyes and cause her pain; but it is the truth. They whispered together, and then they all three laughed—such a silvery, musical laugh, but as hard as though the sound never could have come through the softness of human lips. It was like the intolerable, tingling sweetness of water-glasses when played on by a cunning hand. The fair girl shook her head coquettishly, and the other two urged her on.

[These three brides of Dracula fall upon Harker, but the Dracula storms in and shoos them away. He says:]

“How dare you touch him, any of you? How dare you cast eyes on him when I had forbidden it? Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me! Beware how you meddle with him, or you’ll have to deal with me.” The fair girl, with a laugh of ribald coquetry, turned to answer him:—

[Some short conversation follows, and then:]

“Are we to have nothing to-night?” said one of them, with a low laugh, as she pointed to the bag which he had thrown upon the floor, and which moved as though there were some living thing within it. For answer he nodded his head. One of the women jumped forward and opened it. If my ears did not deceive me there was a gasp and a low wail, as of a half-smothered child. The women closed round, whilst I was aghast with horror; but as I looked they disappeared, and with them the dreadful bag. There was no door near them, and they could not have passed me without my noticing. They simply seemed to fade into the rays of the moonlight and pass out through the window, for I could see outside the dim, shadowy forms for a moment before they entirely faded away.

Then the horror overcame me, and I sank down unconscious.

[Later, in the next chapter:]

As I sat I heard a sound in the courtyard without—the agonised cry of a woman. I rushed to the window, and throwing it up, peered out between the bars. There, indeed, was a woman with dishevelled hair, holding her hands over her heart as one distressed with running. She was leaning against a corner of the gateway. When she saw my face at the window she threw herself forward, and shouted in a voice laden with menace:—

“Monster, give me my child!”

She threw herself on her knees, and raising up her hands, cried the same words in tones which wrung my heart. Then she tore her hair and beat her breast, and abandoned herself to all the violences of extravagant emotion. Finally, she threw herself forward, and, though I could not see her, I could hear the beating of her naked hands against the door.

Somewhere high overhead, probably on the tower, I heard the voice of the Count calling in his harsh, metallic whisper. His call seemed to be answered from far and wide by the howling of wolves. Before many minutes had passed a pack of them poured, like a pent-up dam when liberated, through the wide entrance into the courtyard.

There was no cry from the woman, and the howling of the wolves was but short. Before long they streamed away singly, licking their lips.

I could not pity her, for I knew now what had become of her child, and she was better dead.

The scene where Van Helsing, etc., visit Lucy’s tomb and her former fiancé drives a stake through her heart:

“Take this stake in your left hand,[” Van Helsing said to Arthur, “] ready to place the point over the heart, and the hammer in your right. Then when we begin our prayer for the dead—I shall read him, I have here the book, and the others shall follow—strike in God’s name, that so all may be well with the dead that we love and that the Un-Dead pass away.”

Arthur took the stake and the hammer, and when once his mind was set on action his hands never trembled nor even quivered. Van Helsing opened his missal and began to read, and Quincey and I followed as well as we could. Arthur placed the point over the heart, and as I looked I could see its dint in the white flesh. Then he struck with all his might.

The Thing in the coffin writhed; and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions; the sharp white teeth champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam. But Arthur never faltered. He looked like a figure of Thor as his untrembling arm rose and fell, driving deeper and deeper the mercy-bearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it. His face was set, and high duty seemed to shine through it; the sight of it gave us courage so that our voices seemed to ring through the little vault.

And then the writhing and quivering of the body became less, and the teeth seemed to champ, and the face to quiver. Finally it lay still. The terrible task was over.

The hammer fell from Arthur’s hand. He reeled and would have fallen had we not caught him. The great drops of sweat sprang from his forehead, and his breath came in broken gasps. It had indeed been an awful strain on him; and had he not been forced to his task by more than human considerations he could never have gone through with it. For a few minutes we were so taken up with him that we did not look towards the coffin. When we did, however, a murmur of startled surprise ran from one to the other of us. We gazed so eagerly that Arthur rose, for he had been seated on the ground, and came and looked too; and then a glad, strange light broke over his face and dispelled altogether the gloom of horror that lay upon it.

There, in the coffin lay no longer the foul Thing that we had so dreaded and grown to hate that the work of her destruction was yielded as a privilege to the one best entitled to it, but Lucy as we had seen her in her life, with her face of unequalled sweetness and purity. True that there were there, as we had seen them in life, the traces of care and pain and waste; but these were all dear to us, for they marked her truth to what we knew. One and all we felt that the holy calm that lay like sunshine over the wasted face and form was only an earthly token and symbol of the calm that was to reign for ever.

[And one final thing from a few paragraphs later:]

[T]he Professor and I sawed the top off the stake, leaving the point of it in the body. Then we cut off the head and filled the mouth with garlic. We soldered up the leaden coffin, screwed on the coffin-lid, and gathering up our belongings, came away.

When Van Helsing, etc., rush to the Harker residence to save Mina form Dracula, only to discover they’re too late:

The moonlight was so bright that through the thick yellow blind the room was light enough to see. On the bed beside the window lay Jonathan Harker, his face flushed and breathing heavily as though in a stupor. Kneeling on the near edge of the bed facing outwards was the white-clad figure of his wife. By her side stood a tall, thin man, clad in black. His face was turned from us, but the instant we saw we all recognised the Count—in every way, even to the scar on his forehead. With his left hand he held both Mrs. Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white nightdress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man’s bare breast which was shown by his torn-open dress. The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink. As we burst into the room, the Count turned his face, and the hellish look that I had heard described seemed to leap into it. His eyes flamed red with devilish passion; the great nostrils of the white aquiline nose opened wide and quivered at the edge; and the white sharp teeth, behind the full lips of the blood-dripping mouth, champed together like those of a wild beast. With a wrench, which threw his victim back upon the bed as though hurled from a height, he turned and sprang at us. But by this time the Professor had gained his feet, and was holding towards him the envelope which contained the Sacred Wafer. The Count suddenly stopped, just as poor Lucy had done outside the tomb, and cowered back. Further and further back he cowered, as we, lifting our crucifixes, advanced. The moonlight suddenly failed, as a great black cloud sailed across the sky; and when the gaslight sprang up under Quincey’s match, we saw nothing but a faint vapour. This, as we looked, trailed under the door, which with the recoil from its bursting open, had swung back to its old position. Van Helsing, Art, and I moved forward to Mrs. Harker, who by this time had drawn her breath and with it had given a scream so wild, so ear-piercing, so despairing that it seems to me now that it will ring in my ears till my dying day. For a few seconds she lay in her helpless attitude and disarray. Her face was ghastly, with a pallor which was accentuated by the blood which smeared her lips and cheeks and chin; from her throat trickled a thin stream of blood; her eyes were mad with terror. Then she put before her face her poor crushed hands, which bore on their whiteness the red mark of the Count’s terrible grip, and from behind them came a low desolate wail which made the terrible scream seem only the quick expression of an endless grief. Van Helsing stepped forward and drew the coverlet gently over her body, whilst Art, after looking at her face for an instant despairingly, ran out of the room.

The scene where Van Helsing, etc., wait at Dracula’s London mansion to confront him and things go wrong:

“He will be here before long now,” said Van Helsing, who had been consulting his pocket-book. “Nota bene, in Madam’s telegram he went south from Carfax, that means he went to cross the river, and he could only do so at slack of tide, which should be something before one o’clock. That he went south has a meaning for us. He is as yet only suspicious; and he went from Carfax first to the place where he would suspect interference least. You must have been at Bermondsey only a short time before him. That he is not here already shows that he went to Mile End next. This took him some time; for he would then have to be carried over the river in some way. Believe me, my friends, we shall not have long to wait now. We should have ready some plan of attack, so that we may throw away no chance. Hush, there is no time now. Have all your arms! Be ready!” He held up a warning hand as he spoke, for we all could hear a key softly inserted in the lock of the hall door.

I could not but admire, even at such a moment, the way in which a dominant spirit asserted itself. In all our hunting parties and adventures in different parts of the world, Quincey Morris had always been the one to arrange the plan of action, and Arthur and I had been accustomed to obey him implicitly. Now, the old habit seemed to be renewed instinctively. With a swift glance around the room, he at once laid out our plan of attack, and, without speaking a word, with a gesture, placed us each in position. Van Helsing, Harker, and I were just behind the door, so that when it was opened the Professor could guard it whilst we two stepped between the incomer and the door. Godalming behind and Quincey in front stood just out of sight ready to move in front of the window. We waited in a suspense that made the seconds pass with nightmare slowness. The slow, careful steps came along the hall; the Count was evidently prepared for some surprise—at least he feared it.

Suddenly with a single bound he leaped into the room, winning a way past us before any of us could raise a hand to stay him. There was something so panther-like in the movement—something so unhuman, that it seemed to sober us all from the shock of his coming. The first to act was Harker, who, with a quick movement, threw himself before the door leading into the room in the front of the house. As the Count saw us, a horrible sort of snarl passed over his face, showing the eye-teeth long and pointed; but the evil smile as quickly passed into a cold stare of lion-like disdain. His expression again changed as, with a single impulse, we all advanced upon him. It was a pity that we had not some better organised plan of attack, for even at the moment I wondered what we were to do. I did not myself know whether our lethal weapons would avail us anything. Harker evidently meant to try the matter, for he had ready his great Kukri knife and made a fierce and sudden cut at him. The blow was a powerful one; only the diabolical quickness of the Count’s leap back saved him. A second less and the trenchant blade had shorne through his heart. As it was, the point just cut the cloth of his coat, making a wide gap whence a bundle of bank-notes and a stream of gold fell out. The expression of the Count’s face was so hellish, that for a moment I feared for Harker, though I saw him throw the terrible knife aloft again for another stroke. Instinctively I moved forward with a protective impulse, holding the Crucifix and Wafer in my left hand. I felt a mighty power fly along my arm; and it was without surprise that I saw the monster cower back before a similar movement made spontaneously by each one of us. It would be impossible to describe the expression of hate and baffled malignity—of anger and hellish rage—which came over the Count’s face. His waxen hue became greenish-yellow by the contrast of his burning eyes, and the red scar on the forehead showed on the pallid skin like a palpitating wound. The next instant, with a sinuous dive he swept under Harker’s arm, ere his blow could fall, and, grasping a handful of the money from the floor, dashed across the room, threw himself at the window. Amid the crash and glitter of the falling glass, he tumbled into the flagged area below. Through the sound of the shivering glass I could hear the “ting” of the gold, as some of the sovereigns fell on the flagging.

We ran over and saw him spring unhurt from the ground. He, rushing up the steps, crossed the flagged yard, and pushed open the stable door. There he turned and spoke to us:—

“You think to baffle me, you—with your pale faces all in a row, like sheep in a butcher’s. You shall be sorry yet, each one of you! You think you have left me without a place to rest; but I have more. My revenge is just begun! I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side. Your girls that you all love are mine already; and through them you and others shall yet be mine—my creatures, to do my bidding and to be my jackals when I want to feed. Bah!” With a contemptuous sneer, he passed quickly through the door, and we heard the rusty bolt creak as he fastened it behind him. A door beyond opened and shut.

Minor update: For whatever reason, this post in particular got hit hard with spam comments. Over 400 of them. So I disabled comments for this post.